Previously: The Compass Game.

Welcome to “How Does It Work?”, a new feature here at The Ghost In My Machine that aims to explore how classic forms of divination actually, well, work — both from the believer’s perspective and the skeptic’s. For what it’s worth, I pretty much always fall on the side of the skeptic’s argument; as you probably know by now, when it comes to real-life phenomena, my approach is to see if there’s any possible way something can be explained by natural means before I begin to entertain the idea that it might be supernatural. Here, though, what we’ll do is present both possibilities, then leave it up to you, the reader, to decide which you believe.

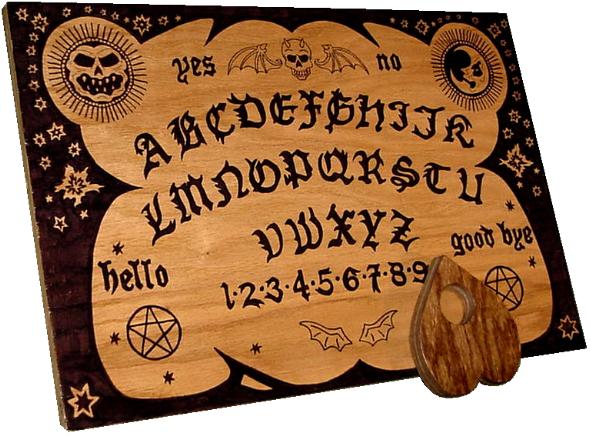

First up: The Oujia board. It’s well-known, it’s accessible, and it’s surprisingly controversial. Let’s take a look.

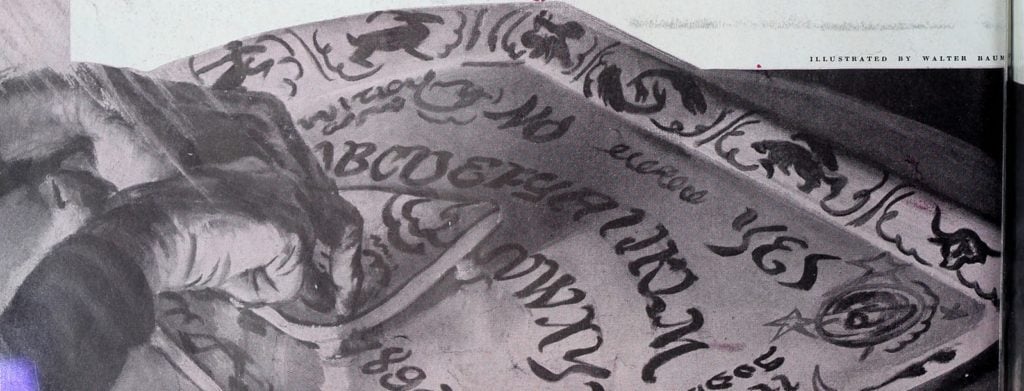

We pretty much all know how Ouija boards are supposed to work, right? You pull out the board, with its letters, numbers, “Yes,” “No,” and “Goodbye” scrawled across its surface; you place the planchette — the little wedge of plastic with a transparent window at its center — in the middle of the board; you place your fingertips gently on the edges of the planchette; and you ask your questions, hoping that someone — or something — might answer: “Spirit, are you there? What is your name? How did you die? What does my future hold?”

[Like what you read? Check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available from Chronicle Books now!]

But regardless as to how they’re meant to work there’s often still a question about how Ouija boards really do work. What’s at play here? Is there really a spirit or entity speaking through it? If so, what sort of spirit or entity is it? Is it benevolent, or malevolent? Or, is it just us, talking to ourselves either on purpose or unconsciously? There’s an argument to made for both sides, of course — the side of the believer, and the side of the skeptic. They’re both convincing, even though those who subscribe to them also often both at loggerheads with each other.

But we’ll get to that in a bit. Before we can talk about how Oujia boards work, we need to talk about what they are — and where they come from.

A Brief History Of The Ouija Board

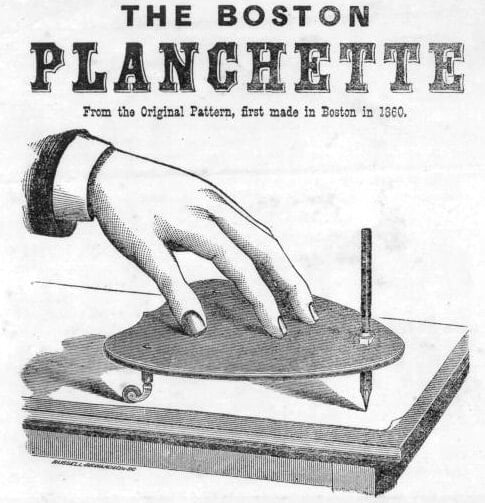

Although the name “Ouija” itself didn’t come round until the early 20th century, the distinctive pieces that make up a Ouija board set — planchette and the board — have existed for substantially longer. The planchette, in fact, may be traced back to Imperial China — although at the time, it was used as a device to facilitate automatic writing, rather than in conjunction with what would come to be known as a talking board.

According to Chao Wei-pang’s 1942 article The Origin and Growth of the Fu Chi, the practice of fu chi or fuji spirit writing dates back to the Liu Sung dynasty or Liu Song dynasty, which ran from 420 to 479 CE. Originally, performing it involved hanging a sieve; later on, however — during the Tang dynasty, which ran from 618 to 907 CE — it became the norm to attach a stick to the sieve instead, thus creating the planchette. During the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644 CE), the use of the planchette in fu chi was further cemented.

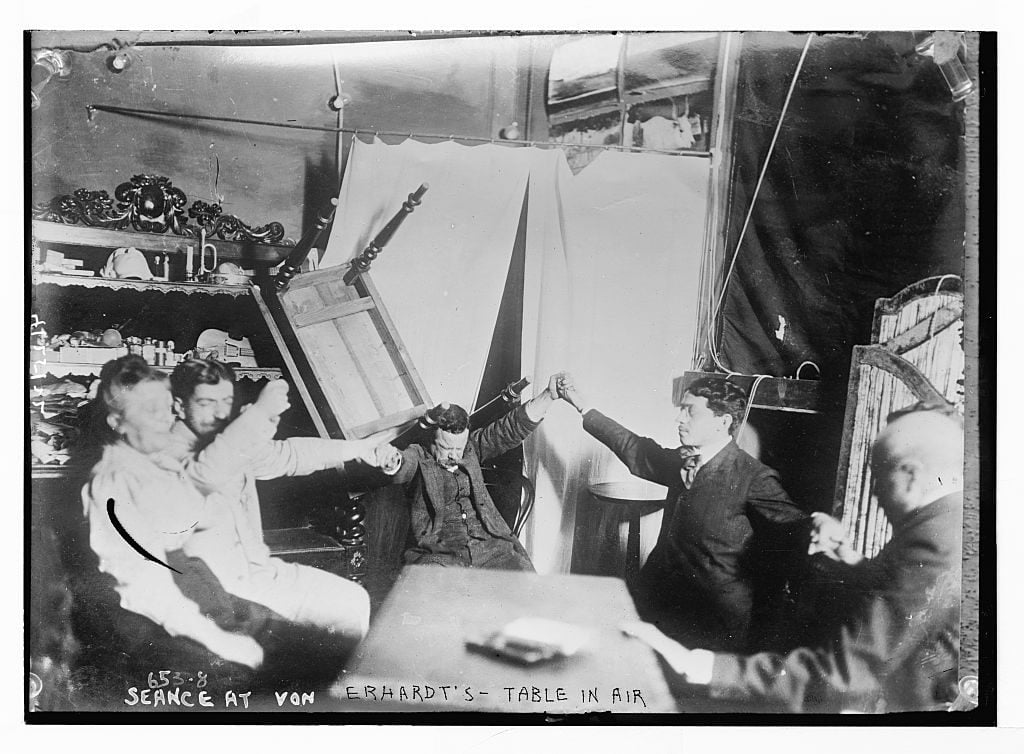

It was in the mid-19th century, however, that the planchette truly came into its own, thanks to the Spiritualist movement. The year pegged to its rise is usually 1848 — the year the Fox sisters, Maggie and Kate, began conducting their seances in Hydesville, New York. However, following the American Civil War, which was fought from 1861 to 1865, the movement gained new momentum as the United States grieved the extreme loss of life that occurred as a result of the conflict. It’s estimated that between 618,222 and 750,000 men died fighting the war, decimating entire generations and making it the deadliest war in American history. In an effort to cope with losing so many — a large proportion of which were incredibly young — many people turned to the possibility of life after death, hoping they might be able to speak with loved ones who had perished.

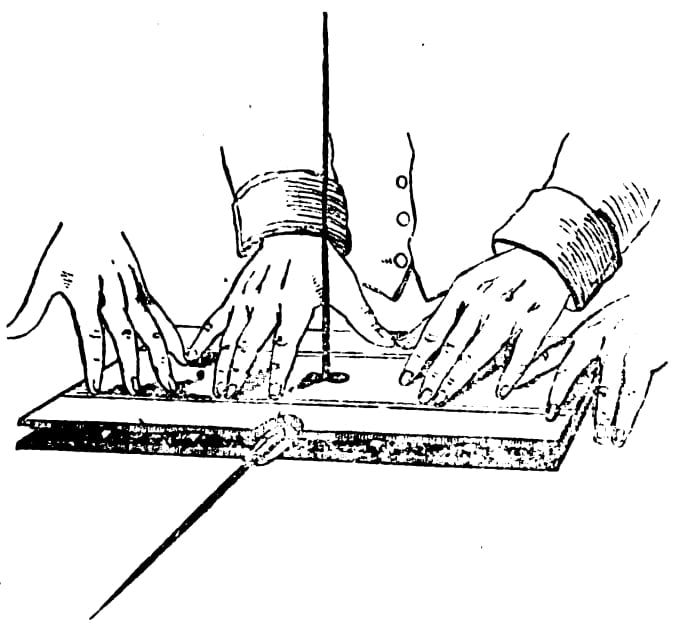

Seances of the era might have included anything from spirit rapping and table tilting to ectoplasm and good, old-fashioned spirit channeling — and, in the case of the latter, that channeling might have been accomplished through automatic writing. Using a planchette wasn’t the only way to conduct an automatic writing session — a medium could simply put pen or pencil to paper and go to town — but by using what was first a small basket, then later a wheeled planchette, fitted with a pencil, all those participating in a seance could contribute to the event. Together, they could ask questions, their fingers lightly touching the planchette, and witness the device writing out responses which seemingly came from beyond the veil.

The “talking board,’ meanwhile, came into use sometime before the 1870s. We don’t know totally when people began writing out the alphabet, the numbers zero through nine, and the words “yes” and “no” on sheets of paper or other materials to use for divination purposes, but according to the Museum of Talking Boards, news reports discussing these homemade devices began appearing at least by 1871. By 1886, the Associated Press had even written about talking boards, which by that point had begun employing planchette-like pieces to use as pointers, which inspired Charles Kennard to bring together a group of investors in 1890 to start the Kennard Novelty Company — a business formed specifically to create and sell commercialized versions of the talking board. The name “Ouija” was allegedly decided upon by the board itself; when Kennard and his group of investors, including Elijah Bond and his sister-in-law, Helen Peters, asked the board what they should call it, it’s said to have replied, “Ouija” — and, when asked what the word meant, replied only, “Good luck.” As Linda Rodriguez McRobbie noted at Smithsonian.com in 2013, however, Peters was apparently wearing a locket featuring a woman’s picture and the word “Ouija” — a woman who may, in fact, have been Ouida, the pseudonym of writer Maria Louise Ramé, whom Peters regarded quite highly inded.

In any event, the Ouija board, henceforth to be sold with an accompanying planchette, was patented in 1891; it hit toy store shelves shortly thereafter, and has remained a popular seller ever since. Similar methods of divination are still often made in a DIY fashion by enterprising individuals at home, though; if you’ve ever played Spirit of the Glass or Spirit of the Coin, they’re fundamentally the same thing — the players draw the board themselves, then use a glass or a coin as the planchette.

So: How does it work? Let’s take a look at both sides.

The Believer’s Argument

Those who subscribe to this argument, which might also be referred to as the Spiritualist theory, believe that Oujia boards do in fact have the ability to channel the voices of spirits, entities, demons, and other supernatural beings. The entities communicate with the earthly world by guiding the planchette — or the users’ hands while they touch the planchette — to spell out words and numbers or indicate “Yes” or “No” on the board in response to questions posed to them. There are, however, a number of beliefs about what might actually be going on here.

It’s possible, for example, that whatever is using the board to talk is able to possess the planchette itself, moving it around almost like a poltergeist might. (In case you need a refresher, a poltergeist — literally a “noisy ghost” in German — is a malevolent spirit that harasses its victims by manifesting physical activity: It can make loud noises; it can tug at people; and, perhaps most tellingly, it can move objects, knock them over, and throw things.) The spirit possessing the planchette may not necessarily be malevolent like a poltergeist (although it certainly could be) — but the ability to move objects in the physical world is one of the identifying characteristics of a poltergeist. The similarities between the two ideas is interesting to me.

It’s also possible that the entity communicating with those using the board has actually possessed the players and is guiding not the planchette, but the players’ hands, which in turn guide the planchette. I would argue that this possibility is a form of mediumship: If, as The Circle posits, there are two primary forms of mediumship — physical and mental — then mediumship accomplished through a Ouija board and a planchette would likely classify as physical mediumship.

As for what kinds of entities believers suspect Ouija boards might attract? Well, that can vary. As the Museum of Talking Boards points out, some believe that most spirits are inherently benign and simply want to pass on information to us. Others, however, believe the board mostly contacts spirits “on the lower astral plane” — this particular area of the astral plane being where violent or malevolent entities reside — thereby making using a Ouija board inherently dangerous.

Either way, though, many people who believe the Spiritualist theory point to events and instances they just can’t explain as proof: The board saying the entity using it was a specific type of person who died in a specific way, which official records of the location in which thee board was used later confirming that such a person’s death occurred on the premises in that fashion; the planchette spelling out information that only one person in the room could have known when that person’s hands weren’t actually on the planchette; and so on and so forth.

The Skeptic’s Argument

On the other hand, though, there’s the skeptic’s argument, also referred to as the Automatism theory: It isn’t spirits moving the planchette; it’s the users of the Ouija board. The key here is the ideomotor effect, a well-documented phenomenon in which “unconscious, involuntary motor movements… are performed by a person because of prior expectations, suggestions or preconceptions,” according to the Critical Thinking Association. First observed in the early 19th century, it was formally identified by English physician William Benjamin Carpenter in 1852 — the phrase itself originating from ideo, meaning idea, and motor, referring to muscular action.

How does the idea apply to Ouija boards? As Aja Romano explained over at Vox in 2017, the ideomotor effect may result from “your brain… unconsciously [creating] images and memories when you ask the board questions.” Wrote Romano, “Your body responds to your brain without you consciously ‘telling’ it to do so, causing the muscles in your hands and arms to move the pointer to the answers that you — again, unconsciously — may want to receive.” Additionally, noted Dr. Chris French at Smithsonian.com in 2013, in the context of a Ouija board, “a quite a small muscular movement can cause quite a large effect” — perhaps explaining our willingness to believe we’re actually channeling spirits.

Indeed, there’s a fairly substantial body of research that supports the idea of the Oujia board tapping into our subconscious. Indeed, several studies conducted out of the University of British Columbia in recent years have found that people find it easier to access information they already have stored in their brain through a Ouija board than they do when asked questions about it directly. You know how sometimes your brain solves problems when you’re asleep? Think of this in the same way: When you’re not focused on the information consciously, your brain can unearth it a little more easily.

I also think there’s a slight variation on the “It’s actually you!” idea that might apply to the whole Ouija board situation: Your unconscious might not be causing you to move the planchette in such a way as to give you the answers you want to receive; you might just be involuntarily twitching, causing the planchette to move with no real rhyme or reason. However, in our endless quest to make sense out of chaos, you might then interpret the results to mean more than they do, constructing a message out of what’s essentially just noise — that is, it could very well be apophenia.

What Do You Believe?

Me? I come down on the side of the Automatism theory — but you probably already knew that, didn’t you? Despite owning and having spent substantial time with a Ouija board in my youth, I’ve never once had an experience with one that convinced me something other than my friends or myself was moving the planchette. Adding to that is the ideomotor effect, which, y’know, is hard to argue with — we’ve got plenty of research proving its existence, and it’s generally a much more plausible explanation than a ghostly or spiritual one.

Still, though: I recognize that for at least some of the folks who believe in the Spiritualist theory, it’s the belief itself that matters, not whether there’s a rational explanation for it. And that’s cool, too — you do you and all that.

But what do you think? Are you a Spiritualist, or an Automatist? Or do you believe in something else entirely? Only you can decide for yourself — which, I would argue, is a power all its own.

***

Follow The Ghost In My Machine on Twitter @GhostMachine13 and on Facebook @TheGhostInMyMachine. And don’t forget to check out Dangerous Games To Play In The Dark, available now from Chronicle Books!.

I’m defos on the side of the skeptics.

There was a Korean show few years ago where they try out different things Myth Buster style but some more mundane things compared to Myth Busters. One of the episodes had to do with Ouija board.

They sought out a bunch of mediums who advertised channelling through Ouija board, and asked them to help them interview some ghosts on film, but blindfolded. The mediums agreed. And while the mediums were blindfolded, the TV crew secretly set the Ouija board upside down. Shouldn’t matter if it’s the spirits guiding the planchette, right? After all, it’s not the ghosts who are blindfolded; it’s the medium. Even if the ghosts were simply possessing the players, they should be able to see through the eyes of the other participants who weren’t blindfolded.

What ended up coming out of the sessions were pure nonsense. The planchette frequently pointed at blank parts of the board, and even when they did hit upon parts with symbols, the culmination of the symbols made absolutely no sense whatsoever.

So yeah. Either the spirits work with Ouija boards in a manner that we’ve yet to hit upon, or it’s all just the players: consciously or subconsciously.

This website vox says an explanation for Ouija boards is the ideomotor effect.

Last night- a friend of mine said that

his mother and her friends used a Ouija board years ago when they were teenagers.

They asked the Ouija board: “is anybody in immediate danger?”

The Ouija board said “yes”

They asked “is anybody going to die soon?”

The Ouija board said “yes”

Later that week- one of them (his mother’s friend) died in a car accident.

He said his mother said she will never use a Ouija board again after that.

Is that a coincidence? But that’s not the first time I read a story like that. Years ago- I read stories like that about other people using Ouija boards. I read those in different websites.

How can the ideomotor effect explain that?

I do not believe in ghosts, but I do believe in tapping into Consciousness as if it’s the World Wide Web. Some are better at it than others and may get into the proper headspace to obtain information they shouldn’t otherwise know. Others may simply be tapping into their subconscious thoughts and “typing” out whatever comes to mind. I do believe that either way, the ideomotor effect is occurring unless someone is intentionally moving the planchette. A good experiment for clairvoyance or telepathy is to ask the players a question they couldn’t know the answer to and see what they get.

in our youth, my sister and I would have that thing flying around the board, spelling things out. One example I remember was my mom couldn’t find the cat and said “ask that thing where the cat is.” The reply: in the attic. Sure enough the cat was locked upstairs in the attic by accident. Another time we were playing with it and it suddenly stopped and spelled out “announcement” and quit. We looked at each other dumbfounded. At that moment dad knocked on our door to tell us he asked his girlfriend to marry him. These events were numerous for us.

I am on the side of spiritualist, but only was after my first experience using a ouija board. I was over at a friends house and we were using it (she is a very big spiritualist, I was a skeptic at the time) and she asked me to remove my hand from the planchette so there was only those two touching it, she proceeded to ask it what the address of my house was. Which there was no way for either of them to know, they had never been there.

And it recited it. Perfectly.

I agree with you.

I have to say, I have used a Ouija board, with a few of my friends. We were messing around and honestly I’m still not sure about what happened. We talked to a spirit, but when we looked it up later, there was actually a man of that name and age who died in the same way the board said. I don’t know whether to believe in spirits or not anymore but I felt like I should share it.

Interesting! Thanks for sharing!

The ideomotor doesn’t rule out spirit communication in at least some cases. In theory, spirits can communicate with our subconsciouses, influencing the ideomotor movements. Pendulum divination works the same way, in the hands of someone who is practiced.

I mean, I still think the vast majority of the time, it’s just the subconscious, because most people have no idea how to contact spirits, and it takes some effort; having a talking board alone is not enough. But I’m willing to grant that in at least some cases, it’s possible for it to be spirits.

I think it works both ways. Like on one occasion, it could just be the Automatism theory, while on other instances, maybe entities of the other world are really summoned over. I’m a strong believer in such stuff.